Tariff War 2.0

Source : katehon.com – July 24, 2025

https://katehon.com/en/article/tariff-war-20

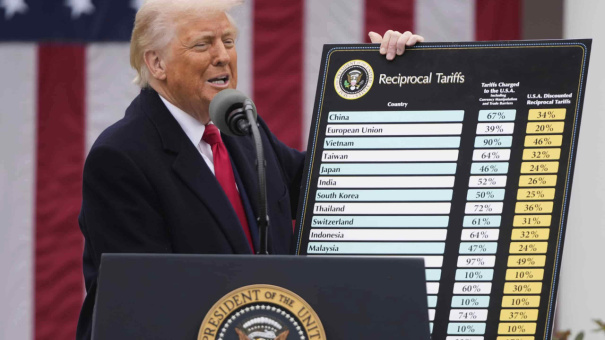

Trump plans to begin the next phase of his tariff war on 1 August after releasing a series of letters to multiple countries’ leaders announcing what the US’ rate will become on that day. The most important of these concern the 35% tariffs on Canada, the 30% ones on the EU and Mexico, and the 25% tariffs on Japan and South Korea. These are among the US’ top trading partners. His letters also threatened to match whatever retaliatory tariffs they might impose on the US and add them to the aforesaid levels.

This approach conspicuously contrasts with the one that Trump is applying towards China, with whom he reached a tentative agreement in early May that he celebrated as a “total reset” in their ties. It remains to be seen whether it’ll hold, but it nonetheless shows that he’s interested in principle in resolving the US’ trade disputes with its top partners. No progress was made with Canada, the EU, Mexico, and many other countries, however, hence why he announced the next phase of his tariff war against them.

As Reuters concisely explained in mid-May here, “Tariffs have been a key part of American economic policy since the country’s founding years”, simultaneously serving to generate budgetary revenue and protect domestic industries. There was a trend towards reducing them after the end of the Old Cold War when globalization was at the forefront of US policy, but the systemic aftershocks of the COVID-19 pandemic and the West’s unprecedented sanctions against Russia from 2022 onward changed that.

Prior to those two world-changing developments, the most significant tariff-related one was Trump’s trade war with China during his first term, which he launched on the pretext of rebalancing the US’ trade deficit but which was really predicated on decelerating China’s rise as an economic superpower. The outcome was inconclusive so he resumed that first phase of his tariff war upon returning to office earlier this year and then expanded the scope to include the entire world before temporarily relenting for talks.

This first phase didn’t achieve the goal that he envisaged, nor could he continue it due to Biden’s scandalous victory in the 2020 presidential election, hence why he resumed everything with gusto to make up for lost time as he and his advisors see it. His self-described “economic revolution” was explained here earlier in the year as aiming to coerce some of the world’s leading economies into further opening their markets to US goods and services together with creating complications for China’s access.

The interim period between the resumption of the first phase of his tariff war and the upcoming second one was meant to hammer out the details of these agreements. Surprisingly, China was the only major economy with which the US reached a tentative deal, which could flip his goals upside-down if successfully implemented. Instead of decelerating China’s rise as an economic superpower, their rebalanced trade deficit could strengthen economic synergy, thus opening up strategic opportunities.

So long as there’s no double-dealing by either and their agreement holds, which can’t be taken for granted and is therefore uncertain, the basis could potentially be built upon which they could consider advancing the “Chimerica”/“G2” scenario. This refers to joint Sino-US global leadership, especially in the economy, but its prospects are dim due to the US’ parallel efforts to more robustly contain China in Asia through military means via its planned “pivot” back to there after the Ukrainian Conflict finally ends.

Nevertheless, the possibility that China and the US could enter into an economic-centric “New Détente” could suffice for scaring the US’ junior partners in the region into reaching the deals that Trump demands independently of the future of his “total reset” with China, which might be the point right now. That’s not to suggest that Trump is insincere about reaching and then respecting an agreement with China, just that their “total reset” serves the purpose of pressuring others into falling in line.

From China’s perspective, alleviating economic-financial pressure from the US, buying time for what might be their inevitable future clash, and exploring ways to offset the aforementioned via the “Chimerica”/“G2” scenario explain why it speedily reached a tentative deal. Even if the US’ regional junior partners ultimately comply with Trump’s demands, the reality of their complex economic interdependence with China could limit the ways in which this harms China’s interests to the US’ benefit.

Just like the US’ couldn’t “decouple” from China during the first phase of Trump’s tariff war, which is one of the reasons why he abruptly reached a tentative deal with it, Japan, South Korea, the Philippines (which is facing 20% tariffs and is embroiled in a tense dispute with China) and Taiwan can’t either. A much more likely scenario than the “Chimerica”/“G2” one is therefore a series of agreements between the US and the aforesaid countries that doesn’t really change much in the grand strategic sense.

The preceding prediction would change if the Sino-US deal collapses, in which case more global economic uncertainty would follow as the US coerces its top trading partners in Eurasia and beyond (such as BRICS co-founder Brazil, which is facing 50% tariffs) into distancing themselves from China. On that topic, it’s important to touch upon the impact that this can have for BRICS, within which China is by far the largest economy. The second phase of Trump’s tariff war is thus arguably against BRICS in part.

He’s railed against this voluntary association of countries, which is united by the goal of accelerating financial multipolarity processes in order to then more effectively reform global governance, on the pretext that it’s secretly dedicated to dethroning the dollar. There’s some truth to this in the sense that accelerating financial multipolarity processes entails BRICS diversifying from most of its members’ hitherto disproportionate dependence on the dollar and the US-led West’s financial ecosystem.

That said, it’s a gradual process that’ll take time to unfold, and most members have no interest in this happening all of a sudden since the resultant global financial shocks could harm their own economies. With that in mind, Trump is exploiting this pretext to publicly justify more pressure upon certain BRICS countries like Brazil and also South Africa, which is facing 30% tariffs. His objective is to reduce the role that Eurasia-centric BRICS’ peripheral (African and South American) members play in the group.

Something similar is seemingly underway with regard to India, whose tariff talks with the US have reportedly been more successful than the previously mentioned countries, especially those last two fellow BRICS members. Trump’s repeated boasts of brokering the Indo-Pak ceasefire during their latest conflict (which Delhi refutes), the incipient US-Pak rapprochement, and continued Sino-Indo tensions have combined with Trump’s tariff war to place plenty of pressure upon India in recent months.

The US dislikes India’s independent foreign policy, both because it’s refused to subordinate itself as the US’ largest-ever junior partner for containing China and since its rapid rise as a Great Power accelerates the global systemic transition to multipolarity at the obvious expense of US hegemony. Despite India’s tense border disputes with China and displeasure with China’s military support of Pakistan, the US has been unable to manipulate India into becoming its vassal on an anti-Chinese pretext.

That’s why hybrid political-economic pressure is now being applied in pursuit of this goal, with a renewed emphasis on economic pressure given the context of Trump transitioning his tariff war into its second phase come August. Even if he can’t manage to subordinate India, he at the very least wants to rebalance their trade deficit, but this could come at the cost of Indian farmers if Delhi is pressured into complying with Washington’s reported demand to open its agricultural and dairy markets to US exports

Farmers are an influential political constituency in India so that could have outsized and unforeseeable consequences for Modi 3.0. He and his government will therefore have to tread carefully and do their best to balance Indian interests amidst the multisided dilemma that the US has placed them into. They might conclude that it’s better to make some economic concessions in exchange for a relief from political pressure, in an attempt to court the US away from Pakistan, and for preferential US arms deals.

Whatever the US’ tariff deals with India, its junior Asian partners, China, Brazil, the EU, Mexico, and Canada might look like, if any are reached with them at all, the common denominator is that Trump is weaponizing the US’ economic leverage over them for political purposes by restricting access to its market. As regards its North American and European junior partners, the US wants to dominate their markets in order to reverse its declining hegemony and thus more assertively lead the “Global West”.

This amounts to a multi-hemispheric sphere of influence within which the US’ sway would be absolutely unchallengeable from within and without. Taken to its extreme, it’s envisaged to include the Caribbean and all of Ibero-America as part of the “Fortress America” concept, thus adding more context to why Brazil is facing 50% tariffs despite the US’ trade surplus with it. In parallel, the US aims to construct a similar economic-centric hegemonic network in Asia, ergo its threatened tariffs against those countries.

Even if only partial progress is achieved, and even that which it might obtain is imperfect owing to these countries’ complex economic interdependencies with China, the US can still succeed in decelerating the decline of its unipolar hegemony to an extent and thus be better positioned for competing with China. The same goes for associated deals with China, India, and the others. All of this is predicated on the US’ response to the global systemic transition to multipolarity.

Therefore, the overarching goal that Trump envisages advancing via the second phase of his tariff war is to counteract the aforesaid processes as realistically as possible given the limitations in doing so due to how much has already unfolded and how long the US waited before pushing back in a concerted way. Simply put, it’s part of a major power play, one which is initially relying on economic means but could evolve into kinetic ones like more proxy wars or even a major war out of desperation if this fails.