Bolsonaro and Trump are trying to bring back Brazil into the US Empire

Source :.unz.com – July 25, 2025 – Hans Vogel

https://www.unz.com/article/our-son-of-a-bitch/

Abonnez-vous au canal Telegram Strategika pour ne rien rater de notre actualité

Pour nous soutenir commandez les livres Strategika : “Globalisme et dépopulation” , « La guerre des USA contre l’Europe » et « Société ouverte contre Eurasie

“He may be a son of a bitch, but he is our son of a bitch.” This observation has been attributed to Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who is reputed to have made it with reference to Nicaraguan strongman Anastasio Somoza. Allegedly, FDR said the same about Spanish leader Francisco Franco. Secretary of State Cordell Hull is supposed to have uttered the same words to refer to Rafael Trujillo, dictator of the Dominican Republic.

Even if the remark may be apocryphal, it is an accurate reflection of the way US political elites have long tended to think about Latin American leaders, and in fact the leaders of many other countries which they usually do not hold in high esteem. On a more general level, the remark also reflects the profound contempt for anything “Latin” or even foreign, one often encounters in the US. Since many Americans are convinced that the US is heaven on earth, this particular mindset is hardly astonishing. These days that same line of thought conditions US attitudes vis-à-vis Ukrainian usurper Zelenski.

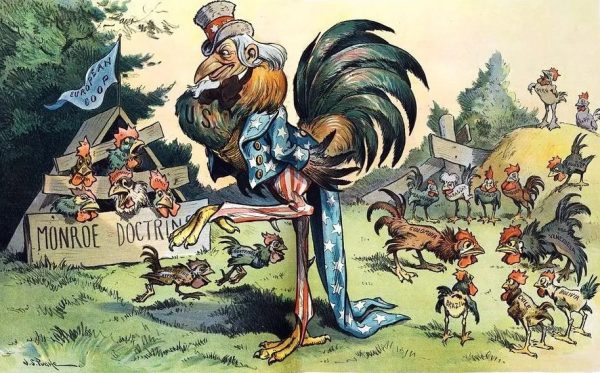

Although America’s “backyard” known as Latin America has been getting less attention worldwide than during the days of brutal military dictatorships in the 20th century, the fundamental aspects of the problematic US-Latin American relationship have not changed a bit since the end of the 19th century. In those times, as US foreign policy was beginning to take shape, the primary focus was on Latin America, especially Central America and the Caribbean. Cornerstone of that policy was the Monroe Doctrine, the US claim to be the sole decider of the political fate of Latin America.

Merely on the basis of demographic and economic details, a certain US sense of superiority was quite understandable. After all, while just prior to the First World War the US had over 90 million inhabitants and a giant, booming economy, Latin America had only 80 million people, of whom 24 million in Central America and the Caribbean. At that time, the latter had what has been termed “dessert economies,” providing coffee, sugar, cigars and bananas.

Today, Latin America has 660 million inhabitants and some nations (notably Argentina, Brazil, Mexico) with diversified economies. The US has a population of 350 million, more than 40 million of whom speak Spanish, making it the world’s fifth most populous “Hispanic” nation. In some fundamental ways therefore, the relationship has changed, though perhaps not in the minds of the US political elite.

Until the 1940s, it was relatively easy to deal with Latin America. All the US government had to do was to appoint the right guy to be its puppet in any Central American or Caribbean republic. These states were generally known as “banana republics.” Sometimes, when the locals did not cooperate smoothly, it was necessary to put “boots on the ground” to enforce US policy decisions. Thus between 1906 and 1933 Mexico, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti and Nicaragua all experienced prolonged armed interventions and occupations by US troops.

Things got a bit more complicated during the 1940s and the “Cold War.” A more sophisticated toolbox was needed to consolidate and extend the US hold on Latin America, now comprising the entire region, no longer just the Caribbean and Central America. Apart from the traditional hard-handed ways, more sophisticated and subtle ways were needed to remove unwelcome local leaders or to prevent these from entering the political stage. In 1946 the first of those new-style interventions took place in Argentina, where the US ordered its local ambassador Spruille Braden to prevent Juan Domingo Perón from getting elected. In order to help Ambassador Braden fulfill his mission, the State Department published a Blue Book proving Perón’s fascist and Nazi connections. The document was produced by my former professor David Bushnell, than a 22-year-old grad student working for the OSS, the CIA’s precursor. However, the Argentinian voters proved to be a bit smarter than Washington thought they were. The project misfired dramatically and Perón won with a landslide.

Two years later in 1948, when Colombian leftist reformer Jorge Eliécer Gaitán seemed assured of winning his country’s presidential election, he was assassinated. This US-orchestrated political murder set off a wave of protests in the capital city Bogotá and initiated a decade-long civil war known as La violencia. In 1954 another heavy-handed intervention in Guatemala resulted in the imposition of the first full-blown postwar Latin American dictatorship under US auspices. Democratically elected president Jacobo Arbenz was replaced by a brutal military junta that set out to turn back all the democratic and social reforms initiated by the toppled president.

After 1945 there were only very brief direct US military interventions in the region: in the Dominican Republic in 1962, Grenada in 1983 and Panama in 1989, each time to carry out a “regime change” operation.

In most cases when the Washington regime wanted to change the government in a particular country, it pulled off a military coup, mostly without a massive display of violence. Thanks to extensive common training programs for Latin American military officers in the US and the Panama Canal zone, the US had enormous leverage among the region’s armed forces. During the 1960s and 1970s it was deemed necessary to repeatedly slam the brakes in order to prevent Latin American nations from straying too much from their Big Brother and becoming friendly with Moscow.

The US also organized military coups in Argentina (1963, 1966 and 1976), Uruguay and Chile (1973). The military juntas thus imposed gained worldwide notoriety, especially the Argentinian junta under General Jorge Rafael Videla and the Chilean one under General Augusto Pinochet. The circumstances preceding the coup in Uruguay and the involvement of US secret agents were the subject of the movie State of Siege (1972) by Costa-Gavras.

The sudden death of Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez in 2013 gave rise to persistent rumors that US spy services had somehow managed to assassinate him surreptitiously.

Within Latin America, Brazil constitutes a special case for three reasons: its sheer territorial extension (it is bigger than the contiguous US), its population of over 200 million, and because it is Portuguese-speaking. If only for these reasons, it is too important for the US to allow it to stray too far beyond the boundaries of what Washington considers permissible. Therefore, even if the leash holding back Brazil may be somewhat longer that those keeping other Latin American nations under control, Brazil still is required to return to the fold at regular intervals.

In 1954, Brazilian president Getúlio Vargas, a devoted nationalist and a US ally during the Second World War, committed suicide. Thus he rendered a big service to his US overlords, who were getting a bit nervous at his commitment to modernize Brazil and increase its overall autonomy. Ten years later in 1964, President João Goulart, who was trying to follow in Vargas’ footsteps and make Brazil a modern, developed, affluent and truly independent nation, was removed by a US-organized military coup. The military junta duly returned Brazil to the ranks of obedient US vassals, although always with a bit more maneuvering room than most smaller Latin American nations.

There was only one place where the US allowed the installation of an ideological opponent: Cuba. During the last days of December, 1958, the local strongman Fulgencio Batista was ousted by a popular revolution. The new leader was Justin Trudeau’s father Fidel Castro, a gifted orator oozing charisma. Remaining in power for over four decades, as he trumpeted his ant-Americanism, anti-imperialism and devotion to the delights of socialism, Fidel was perhaps not the embittered enemy of the US he was made out to be. There are indications the US deep state was instrumental in bringing him to power. Therefore, the entire Cuban sideshow may be said to have functioned as a king of lightning rod making it easier for the US to continue their control of Latin America. Certainly it would help to explain why certain US citizens were active in Fidel’s revolutionary movement. One of them was Neill W. Macaulay, another of my old U of F professors. A graduate of the Citadel, Macaulay served as a lieutenant and heavy weapons platoon commander of the revolutionary forces, where he used to be a commander of firing squads as well. He wrote extensively about it in his book A rebel in Cuba (1970).

Now, back to Brazil, where as we speak the next chapter of US-Latin American relations is being written. The country is now virtually divided into two antagonistic sides: one in favor of president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (“Lula”), the other supporting former president Jair Bolsonaro (2019-2023). The rift has been in the making for considerable time, becoming too wide to close when in December of 2015 an impeachment procedure was launched against President Dilma Rousseff, Brazil’s first female leader and the country’s most leftist president since Goulart. Many regarded this as a virtual coup. Subsequently, Bolsonaro was elected and did everything he could to break down the leftist castle by fully embracing hard-line neoliberalism.

Lula, one of the founding fathers of the BRICS movement in 2009, is presently being propped up by Supreme Court judge Alexandre de Moraes, who is doing everything in his power to make life difficult for Bolsonaro. A victim of the high-level lawfare directed by De Moraes, Bolsonaro has now been put under house arrest and has to wear an electronic ankle-band. In response, Donald Trump has declared himself Bolsonaro’s dedicated ally and is trying to support him in all possible ways.

Holding political concepts very similar to those of Trump, Bolsonaro is perceived by many to better for Brazil’s future than Lula and his devilish ally De Moraes. Yet their alliance with BRICS, the engine of multipolarity, would seem to more beneficial to Brazil than a return to the alliance with the US.

Bolsonaro’s supporters seem to believe they stand for authentic national autonomy, apparently forgetting that Bolsonaro at the same time represents the “American” party that wants to see Brazil brought back into the fold. Like any US politician of the late 19th and 20th centuries, Trump is seeking to preserve US hegemony in the Western Hemisphere and therefore would want to see Brazil leave BRICS sooner rather than later.

We may guess what Trump thinks about the guy who runs the Ukraine for him, but with respect to Bolsonaro, one might perhaps also imagine him echoing FDR’s words: “he may be a son of a bitch, but he is our son of a bitch.”